This intensely beautiful New Kingdom tomb has a new digital life in the metaverse (if you’re a believer in such things), and this post records the process.

It’s an important post for understanding digitization or 3d capture since the tomb was published across several different online platforms, and the audience reached by each platform informs how we capture and publish cultural heritage data today. Specifically, we’ll look at Matterport, Sketchfab, and Google Arts & Culture.

It’s also relevant because the digital capture of the Tomb of Menna was shared virally and has been visited virtually over 3,000,000 times as of writing.

It was first shared during the early months of the worldwide pandemic shutdowns in 2020 and since has been featured by the American Research Center in Egypt in their virtual tours as well as by several other publications. After the initial traffic, a community of consistent visitors views the space virtually each month.

The digitization was commissioned by the American Research Center in Egypt as a part of their “Preserving Egypt’s Layered History” exhibition project about their work. This capture provides access to view distinctive and important areas of the tomb that are gated off as well as a consistent record of the state of the tomb during the moment of capture because there is concern about the impact of continued tourism on the wall paintings.

The Tomb of Menna and its Conservation

The Tomb of Menna is one of the most elaborately decorated and best preserved ancient Egyptian tombs–the enduring color of the wall painting is unlike any other. The tomb is in the Valley of the Nobles on the West Bank of Luxor, Egypt, and dates from the 18th dynasty during the rule of Amenhotep III, the pharaoh known for his building at Luxor and Karnak temples.

Little is known about Menna, but his tomb describes him as a scribe and overseer of the fields that belonged to the pharaoh and the temple of Amun-Re. Menna is depicted on the walls of his tomb as wearing the sbyw-collar, or the Gold of Honor, that indicates he was formally recognized by the king.

The tomb was conserved by egyptologist and professor, Melinda Hartwig, via an international collaboration between Georgia State University, the American Research Center in Egypt, several European centers of archaeometry, the Supreme Council of Antiquities, with support from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

In her book about the project, The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb, Hartwig writes, “Menna would have supervised a number of field scribes and reported to the central field administration in the office of the granaries of the pharaoh . . . From the scenes depicted in his tomb, we can see that Menna supervised delegations who measured the fields, brought defaulters to justice, inspected field work and recorded the yield of the crop.”

In the elaborate scenes on the walls of the tomb, however, the face of Menna is destroyed. In ancient Egyptian religion, the image of the person embodied their spirit, so at some point, the tomb was sabotaged, and the face of Menna erased.

You can get the full story about the history of the tomb and the project undertaken by Hartwig in her online lecture at the American Research Center in Egypt here:

Also, to learn more about the conservation project directed by Hartwig and sponsored by grant resources from the U.S. Agency for International Development, check out the project description the American Research Center in Egypt.

Without further ado, the next stages of this post cover how the digitization process and display of results across platforms.

Field Capture of the Tomb

The data capture of the tomb was completed by gathering laser scan point cloud data partnered with over 4,000 photogrammetry photos. The capture was in-part experimental, using new technologies to both record and display data, specifically with the Matterport laser scanner.

While photogrammetric capture for cultural heritage recording has been well practiced, using the Matterport software and laser scanner to record data was not as frequently used, but it was tested at the Tomb of Menna because the presentation of the data across platforms (and low-bandwidth internet connections) on the Matterport software was well-developed.

The photography was undertaken by master Egyptian photographer with the Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities, Ayman Damarany, to generate a high resolution 3d model. Photos were taken with about 80% overlap for the highest resolution results.

The laser scanner data was also included from your illustrious author to scan the entire tomb to sub-millimeter level accuracy. The laser scan data point cloud was then added to the photogrammetry data in processing.

The entire capture process took one day, with a few tea breaks and midmorning break to eat the local ta’amiyah (filafel) and ful inside half of an aish baladi (pita bread) in the traditional fashion. Egyptian ta’amiyah is distinct from other types of filafel in the middle east because it’s made with fava beans instead of chickpeas.

The camera was a Canon EOS 6D and laser scanner was a Matterport Pro 2.

Processing and Editing the Model

After data capture, the higher resolution 3d model was processed by the brilliant Egyptian 3d artist from Alexandria, Mohamed Abdelaziz. This video is a screenrecord of his exploration of the finished tomb in Unreal. The laser scan data was able to viewed independently on Matterport.

Mohamed used the 4,000+ photogrammetry photos and laser scan pointcloud data to process a high resolution 1:1 scale digital version of the original space. That’s where things got creative.

Portions of the capture were difficult to render, such as the very thin rails that the conservators added to protect the wall paintings, so in the final capture, these are removed.

Additionally, the door and other shelving included in the entryway to the tomb were removed for the purposes of display in the final model, and the white rock on the floor that was added by the conservators was replaced with a rock texture that is closer to the original floor of the tomb.

With this added, the final version of the high resolution 3d model was ready for publication on Sketchfab.

Three Platforms, Three Audiences

After processing the 3d data for the final version of the model, the results for ARCE were published as a part of their digital exhibition and other educational programming materials. The goal described by ARCE was to showcase some of the conservation projects that they sponsored over the past years from the different cultures represented in Egypt.

As a result, with both the photogrammetric and Matterport capture, there was much more data to work and options for publication–so we tested quite a few.

You can compare the results for yourself back-to-back here:

Matterport

You can view the results for the Matterport capture embedded here or if you’re reading on email, at this link: https://www.arce.org/tomb-menna

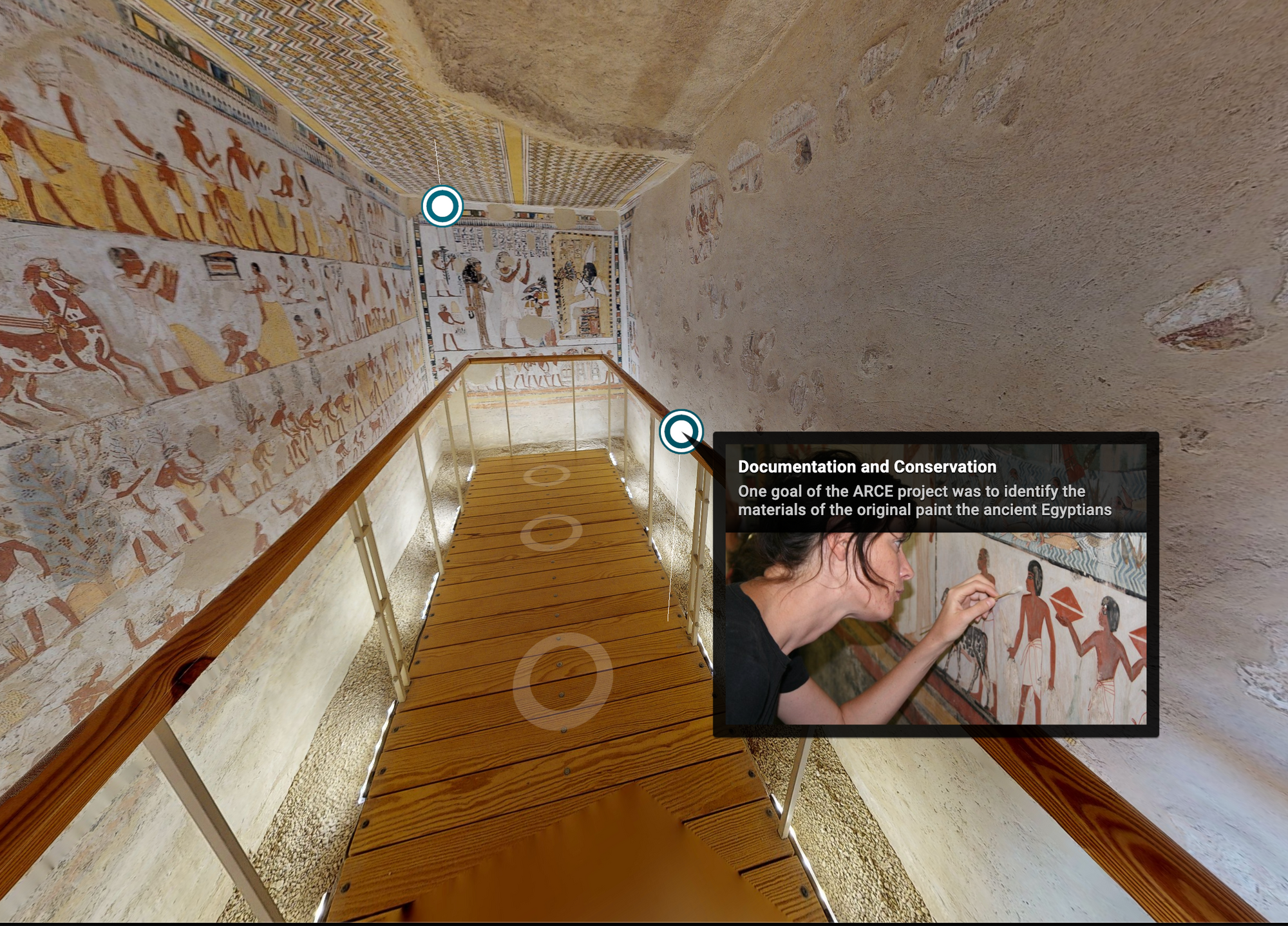

The team at ARCE created annotations for exploration of the Matterport tour with multimedia content for telling the story of how the Tomb of Menna was conserved.

They additionally created a self-guided Showreel virtual tour included with the Matterport tour.

The Matterport tour is controversial in some ways because the technology is more often used for recording of real estate and other industrial use cases. However, the technology opened many doors for ARCE in their eventual publication.

Specifically, during the worldwide pandemic shutdowns at the start of 2020, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities chose to share the Matterport version of the 3d recording as a part of their #StaySafe #StayHome #ExperienceEgyptAtHome campaign.

The combination of the 360 photos and low-resolution 3d scan data offered a photo-realistic virtual tour experience to visitors that was the most accessible internationally of all of the presentation options.

As a result within a few weeks, the Tomb of Menna Matterport model had received over a million virtual visits, far more than any previous virtual tour or 3d capture for the project.

The Matterport model was shared virally as well and has over 54,000 shares and engagements on Facebook alone at the time of writing.

Anecdotally, while in the field and sometimes on lower-bandwidth connections or on older smartphones, the Matterport model still loads the fastest and is by far the most performant of any of the platforms.

Sketchfab

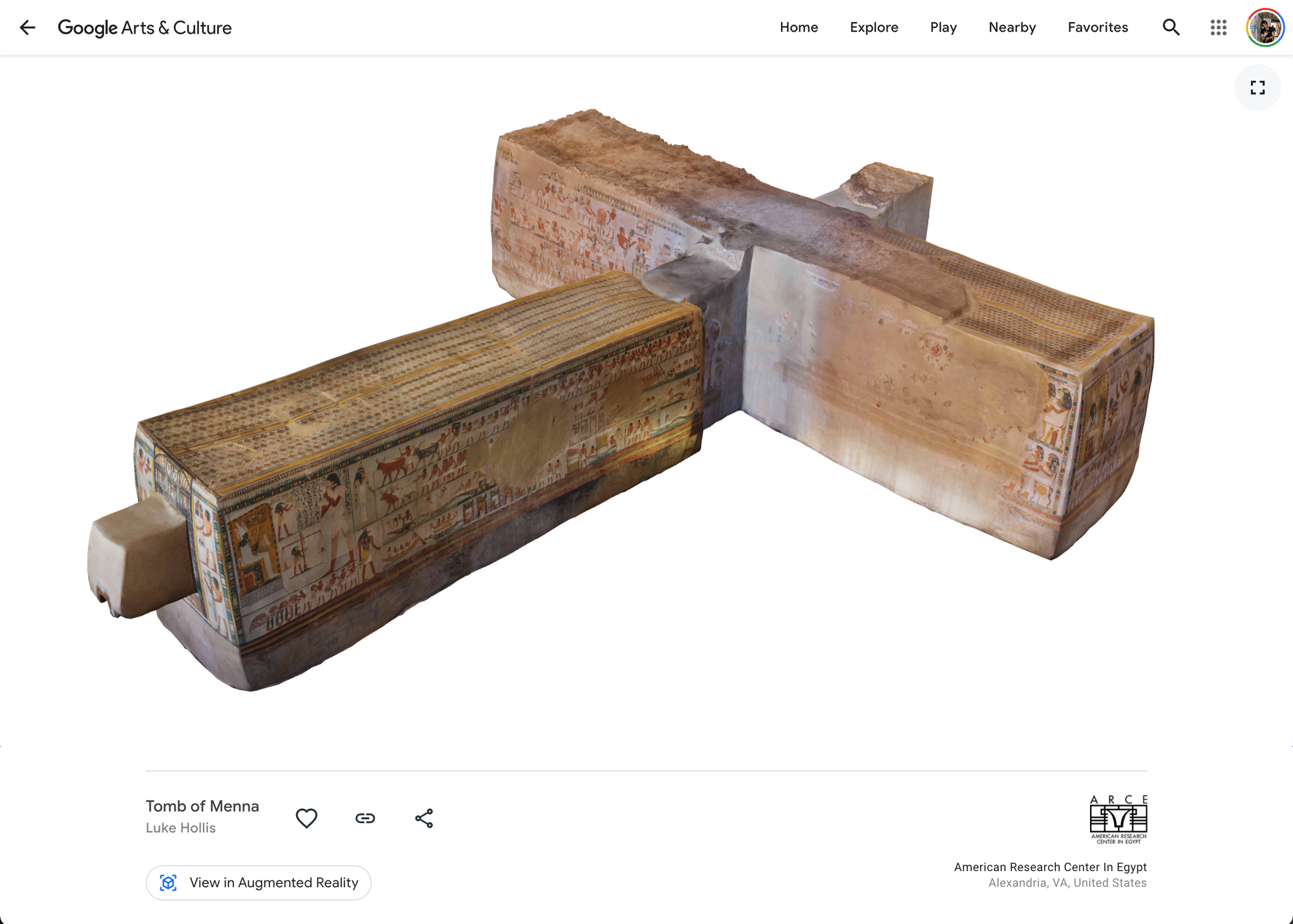

The final render of the 3d model created by Mohamed Abdelaziz was reduced in size for presentation on Sketchfab. Specifically, Mohamed decimated the mesh data of the photogrammetry capture, retopologized the model, and then UV unwrapped the results and published a version of the model that was about 1/10th of the size of the original export from the photogrammetry software.

The photogrammetry was beautifully rendered and includes the highest amount of detail of any of the models. It also is easiest to use for positioning to view all different sides of the model–you can test for yourself navigating the model and viewing all sides, even the exterior of the model and entryway.

Google Arts & Culture

Finally, the various data captured through both photogrammetry and the laser scan was presented in the digital exhibition on Google Arts & Culture.

The 3d model is viewable in Augmented Reality in your space if you’d like to walk around inside it or see it in the world otherwise through the “magic window” of your smartphone.

Additionally, the Matterport capture was able to be published on Google Streetview and the Google Streetview walkthrough can be the subject of multimedia narratives, so the ARCE team used our Matterport capture to make these fascinating guided tours:

Conclusion: Challenges of 3D Data Capture and Overcoming the Digital Divide

Moving forward, the various experimental captures at the Tomb of Menna as well as the viral share of the virtual tour changed the way that we practice digitization and 3d capture. We now have a consistent emphasis on data presentation at multiple layers, including one specifically designed for the general public on a low-bandwidth internet connection.

I’ve debated this often and think it’s an important problem to end on: especially with 3d data, it’s still really difficult to open and view large results from high quality 3d data capture, much less share them over an internet connection. I’d argue that making 3d data accessible as much as possible is an important responsibility of cultural heritage 3d capture and capturing a version of the space that is easily accessible on lower-bandwidth connections or older smartphones is one way to overcome that.

Capturing 3d data for sharing on low-bandwidth connections is an important investment in the local communities where data is captured that might have a hard time accessing the data otherwise.

This bridges into the subject of the digital divide that I’ve written about before (and is defined at places like the Stanford CS Dept):

The idea of the “digital divide” refers to the growing gap between the underprivileged members of society, especially the poor, rural, elderly, and handicapped portion of the population who do not have access to computers or the internet; and the wealthy, middle-class, and young Americans living in urban and suburban areas who have access.

While there is no easy answer to this complicated issue, one way that we combat the digital divide at Mused is by providing the easiest access to the 3d content that we capture. As we have immense privilege to work at heritage sites around the world, we feel like this is our social responsibility and a part of our investment back into local communities.

As a result, our capture methodology is unique! We still preserve all of the higher end photogrammetry and highly accurate sub-millimeter 3d scanning data while making versions available that work on older smartphones. And that secret sauce is the subject of a future post.

Special thanks with this post to our outstanding and forward-thinking partners at the American Research Center in Egypt! They’re consistently seeking to test new ideas and methodologies with their digital programming. You can see more of their virtual tours at https://www.arce.org/virtual-tours

✉️ Signup for more information about virtual tours and metaverse capture delivered to your inbox by entering your email below!