(Un)Complicating the Story of the Discovery of the Tomb

This post is a special feature by Egyptologist Tessa Litecky, in honor of a virtual tour of the Tomb of Tutankhamun for an upcoming exhibition between the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East (HMANE) and Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities in Egypt.

We’re proud to share the guided virtual tour preview. If you’re stateside in Boston or in Egypt, please visit this phenomenal monument and exhibitions at the Grand Egyptian Museum and the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East as they open.

Without further ado, go on a virtual Guided Tour of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings here:

This is in celebration of the 100 year anniversary of the discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in the modern times. We sincerely hope that you enjoy!

Also check out the awesome History of Egypt Podcast created by Dominic Perry about Tutankhamun.

? Podcast Guide

(Un)Complicating the Story of the Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb

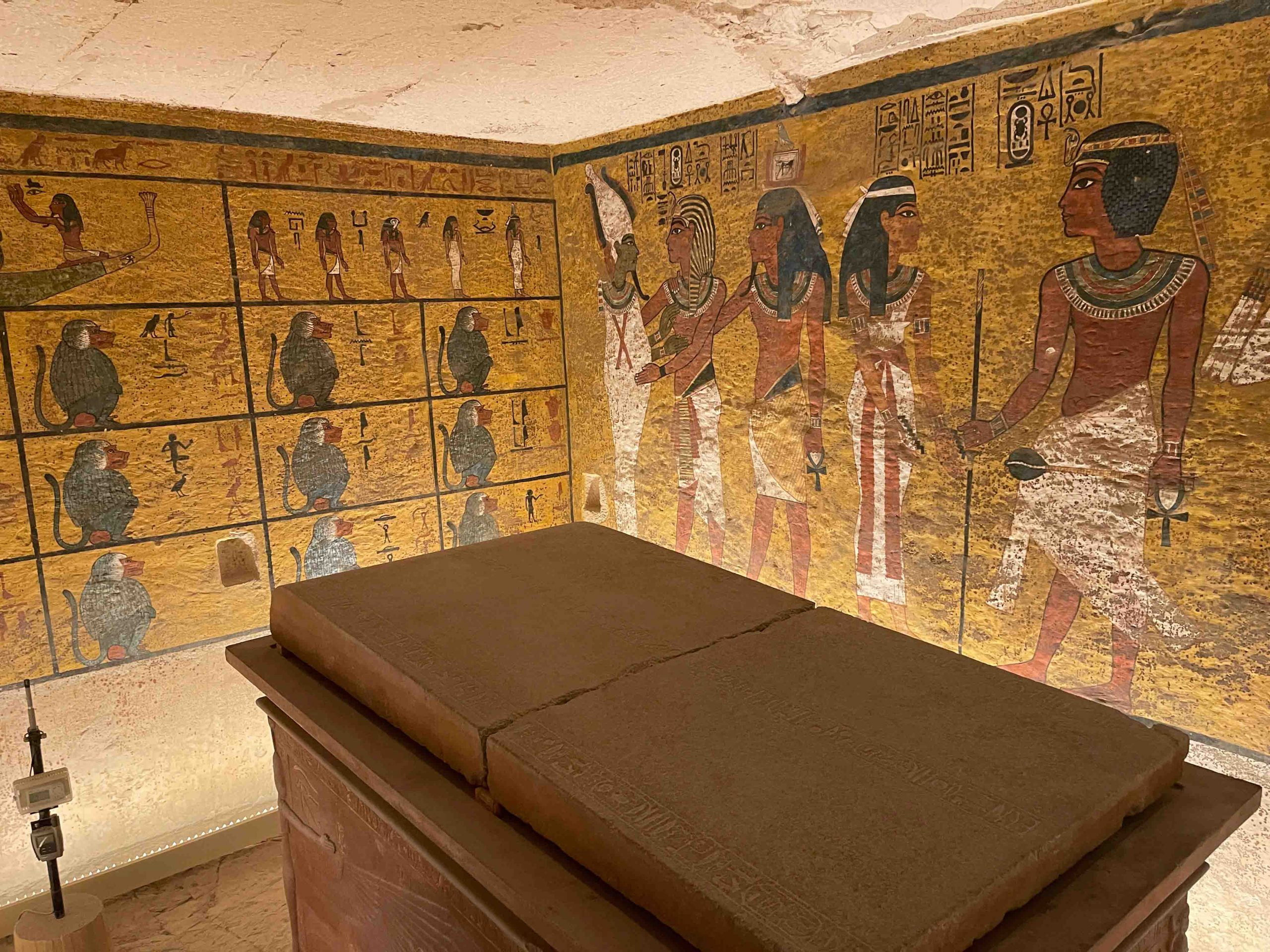

The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun changed the world. Hidden away safe from tomb robbers for millennia, this discovery was so significant because it was something extremely rare in archaeology: an undisturbed royal tomb. What archaeologists found was a treasure trove of grave goods and personal items belonging to the young king who lived during one of Egypt’s most prosperous periods. Inside was furniture, chariots and trapping, statues, clothing, jewelry, as well as Tutankhamun’s mummy, coffin, and the famous gold mask.

To explore the tomb and see the size for yourself (without all those artifacts) visit our guided tour.

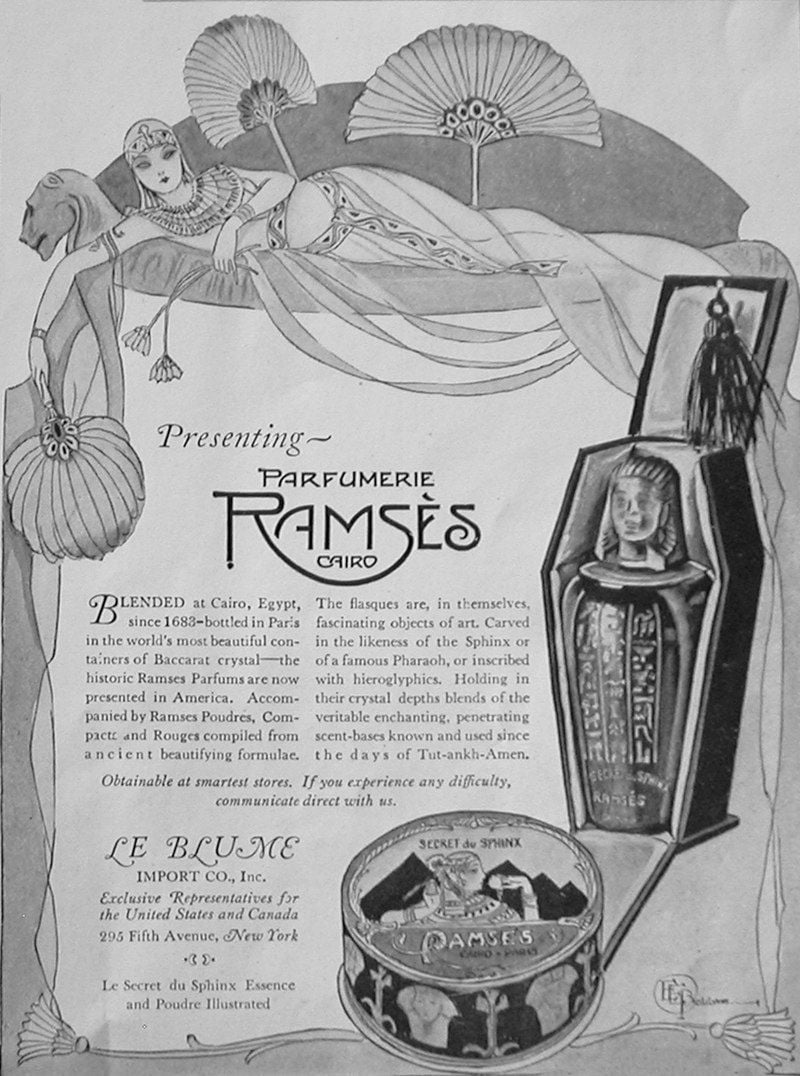

What Howard Carter glimpsed through that small opening into the tomb in November 1922 would continue to fascinate archaeologists and researchers for a century. However, the events of that day would create an unforeseen ripple effect that spread far beyond the arena of Egyptology. The discovery of this enigmatic king and his tomb was tinder for the explosion of Egyptian nationalism, and sparked a global wave of Egyptomania – an obsession with all things Egypt.

Tut-mania inspired films, books, and music. This song, “Old King Tut”, was recorded in 1923 by the musical duo Billy Jones and Ernest Hare. Pretty catchy, don’t you think? Or maybe you prefer Steve Martin’s satirical bop “King Tut” from 1978…?

History would remember two men behind this extraordinary discovery: the archaeologist and Egyptologist, Howard Carter, and his financial backer, Lord Carnarvon. But the story of Tutankhamun’s tomb encompasses an entire cast of characters who have been overshadowed by the two men at the center. On the centennial of the discovery, we wanted to take the time to tell the story of the other people involved in the discovery of the world’s most famous tomb.

Almina Wombwell

Lord Carnarvon is acknowledged as the dedicated patron of Carter and his excavations, but the real money came from a somewhat surprising source: his wife. Carnarvon married Almina Wombwell in 1895. She was the daughter of a British army officer, Captain Frederick Charles Wombwell, and his French wife, Marie. However, the rumor was that Almina’s biological father was none other than Alfred de Rothschild of the famous Rothschild banking family. Fredrick Wombwell was listed on Almina’s birth certificate, but Alfred de Rothschild acted as her guardian and enabled Almina’s marriage to Lord Carnarvon by providing a £500,000 dowry, which is the equivalent of about £41 million or $48.5 million today.

This extraordinarily large injection of cash allowed Lord Carnarvon to pay off his debts, maintain his impressive estate at Highclere Castle, and provide financial backing for Carter’s excavation work in Egypt, including the salaries of local Egyptian workers.

Without Almina’s fortune and the wealth of the Rothschild family, Tutankhamun’s tomb may have never been discovered. Almina traveled to Egypt with her husband often but, unfortunately, was not present at the opening of the tomb due to an ill-timed toothache. However, her daughter, Lady Evelyn, was there with her father.

While it was Lord Carnarvon’s passion for Egyptology that brought the couple back to Egypt year after year, Lady Carnarvon herself became enthusiastic about the excavations and the possibility of discovery. In his book, Carter recalls discovering a cache of alabaster jars after a rather disappointing few months with very few finds. Lady Carnarvon was so excited, she began to dig the beautiful jars out of the dirt with her bare hands. Even after her husband’s untimely death in 1923, Almina continued to fund Carter’s work for several years.

Marriages between male British aristocrats and wealthy women were common around the turn of the century. These lords, dukes, and earls enjoyed the large fortunes brought into the marriage by their wealthy, often American, wives. The women gained a very fashionable title and guaranteed a desirable position in high society as part of the British aristocracy. It was new money and old money coming together to provide exactly what the opposite desired. These so-called “dollar princesses” of the Gilded Age included the mother of Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Consuelo Vanderbilt, whose sizable dowry essentially saved the famed Blenheim Palace from ruin.

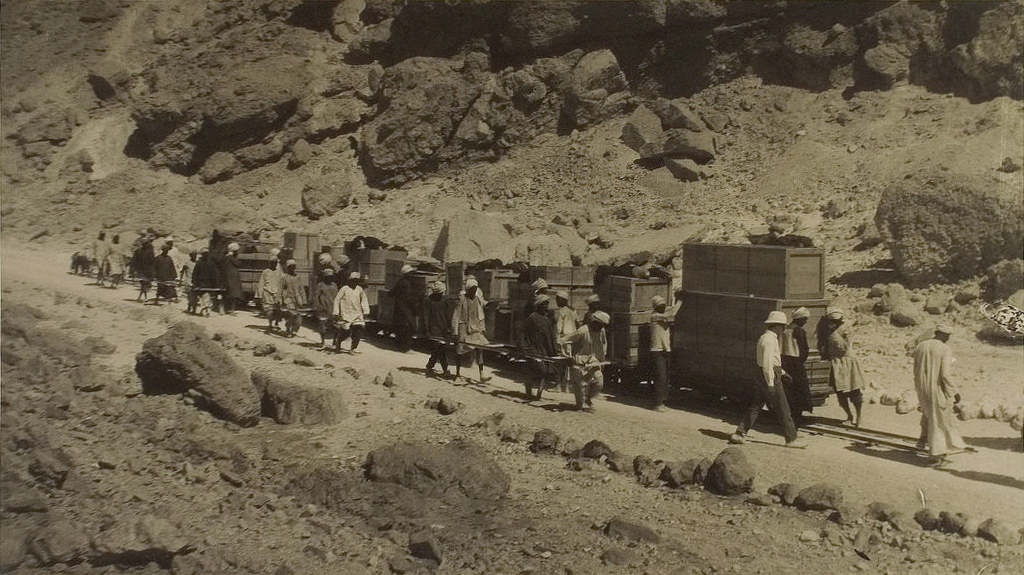

The Egyptian Workmen and Ahmed Gerigar

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the labor of excavating Tutankhamun’s tomb and removing the extraordinary treasures found within was carried out by Egyptian workmen. Ahmed Gerigar acted as foreman, leading teams of local Egyptian workers. No doubt the physical toll of excavating in the hot, dusty conditions of southern Egypt would have been taxing, especially for the young boys who carried baskets of dirt and rocks for hours on end.

There has been an increasing effort to recast the story archaeology in the early 20th Century with a greater appreciation for the unique contribution of the local people who brouth with them their specialized knowledge of the region and the area’s history.

Recently, one of Ahmed Gerigar’s descendants attended the reopening of Howard Carter’s house in Luxor. The Bodleian Library in Oxford opened an exhibition last April called Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive. Using the vast archive of the Griffith Institute, the exhibition “brings to life the complex stories of the discovery, excavation, documentation and conservation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, including often overlooked Egyptian members of the archaeological team.”

By all accounts, Carter was actually a staunch supporter and defender of his workmen and made a point to acknowledge their contribution. In Carter’s book, The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen, he writes in the preface,

Last of all come my Egyptian staff and the Reises who have served me throughout the heat and burden of many a long day, whose loyal services will always be remembered by me with respect and gratitude and whose names are herewith recorded: Ahmed Gerigar, Hussein Ahmed Saide, Gad Hassan and Hussein Abou Owad.

However, we cannot separate this relationship from the colonial context of 1920s Egypt. The photographic record of the excavation documents the workmen in action, but none are identified or given names.

Hussein Abdel-Rassoul: The Boy with the pectoral

One of the few images in which the Egyptian subject has been identified, and made very famous, is the photograph below of Hussein Abdel-Rassoul. The official photographer of the expedition, Harry Burton, wanted to show how this pectoral would have looked on the shoulders of the young king. So, he grabbed a waterboy, adorned him with this priceless artifact and snapped this iconic image. It was captioned “An Egyptian boy wearing one of Tutankhamun’s pectorals”, but years later, Abdel-Rassoul identified himself as the boy in that image.

Abdel-Rassoul also claims that it was actually him and his donkey who first discovered the tomb. Carter’s diary records the actual discovery of the tomb only in the most general terms, which has left room for ongoing theories and rumors. In his book, Carter only writes, “Hardly had I arrived on the work next morning (November 4th) than the unusual silence, due to the stoppage of the work, made me realize that something out of the ordinary had happened, and I was greeted by the announcement that a step cut in the rock had been discovered underneath the very first hut to be attacked.” Abdel-Rassoul’s account is that, while transporting water by donkey, he stepped into a hole revealing the first traces of the entrance to the tomb. While others have credited a horse for finding the first step, or believe that it was simply uncovered during the course of normal excavations, Abdel-Rassoul and his descendants have devoted themselves to their version of history.

Complicating History

One of the reasons Hussein Abdel-Rassoul’s story may have been deemphasized in the historical record is because he comes from a family of infamous “tomb robbers” (a profession as old as tomb-building itself). The story goes that the family stumbled upon a royal cache of mummies and grave goods on their land on the West Bank of Luxor. They sold these artifacts to foreign visitors and tourists making a small fortune for the family.

Alternatively, in his recent book, Egyptologist Bob Briar lays out evidence that Howard Carter actually stole artifacts. Objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb have popped up in collections around the world, spurring rumors that Carter and his team lied and smuggled artifacts out of the country and circumvented the Egyptian authorities. So, essentially, also a tomb robber?

Even as we begin to untangle the full story of the discovery of the famous boy-king’s tomb, the characters we uncover are at one time inspiring and disappointing, both simply and problematic. Their contributions to Egyptology are simultaneously groundbreaking and possibly destructive. This doesn’t make it easy to build a nice, clean narrative, but isn’t that what makes history so interesting?

✉️ If you enjoyed this post and want to receive more digital heritage and virtual guided tours to your inbox, sign up for more information about virtual tours and metaverse capture delivered to your inbox by entering your email below!

Footnotes

- Carter, Howard; Mace, Arthur (1923). The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen, volume 1. London, p. 83.

- https://visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/event/tutankhamun-excavating-the-archive

- The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen, p 87.

- Brier, Bob (2022). Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World. Oxford University Press.

Additional Sources